Books in Translation

Shakespeare, Jane Austen, Charlotte Brontë—heck, even good old J.K. Rowling—these are all authors that can be enjoyed by English-speakers without having to give a second thought to discrepancies in translation. Imagine reading Shakespeare in translation—how could they possibly capture the rhythm of the iambic pentameter? Books written originally in English and not translated have the advantage of not losing the true meaning in their words and phrases. Readers get exactly what the author wanted them to imagine and feel from the text.

In the same vein, there are countless writers that have authored “classic” books we read in English, but were originally composed in an entirely different language. Jean Paul Sartre, Leo Tolstoy, Federico Garcia Lorca—the list goes on. The English versions of their works are considered works of such intricacy and high caliber, but just how much is lost in translation?

Translation opens up a whole new can of worms—how can translators possibly capture all of the nuances of the original text and give them cultural significance? How do they imply accents or the native sentence structure?

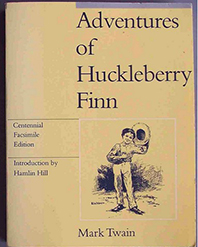

Notable Books in Translation

If you’ve ever read Huckleberry Finn (Mark Twain), you know that Jim’s dialect is one of the defining traits of his character. But how does that carry over in translation?

As scholar Raphaele Berthele outlines in his paper on the subject, German translators took a three-pronged approach to the matter: they focused primarily on the social relationship between the various language varieties (in this case, Jim and Huck’s), the author’s attitudes concerning these relationships, and finally, the author’s original intention in using these non-standard linguistic patterns.

In Huckleberry Finn, it’s clear that Jim’s dialect is a marker of his “otherness”—and the translators took that as a priority as they created their interpretation of the text.

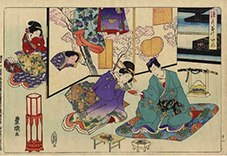

The Tale of Genji

The Tale of Genji (Murasaki Shikibu) is a 1000+ page epic that is considered to be one of the world’s first novels. It has three major English translations; written by Arthur Waley, Edward Seidensticker, and Royall Tyler respectively.

The three translations greatly differ—Waley took a much looser approach, striving to capture the personality of the novel, rather than the exact words. Both Seidensticker and Tyler were much more faithful to the original Japanese; Tyler’s even manages to capture the roundabout sentence structures that characterize the Japanese language (at least to us English speakers).

The three translations greatly differ—Waley took a much looser approach, striving to capture the personality of the novel, rather than the exact words. Both Seidensticker and Tyler were much more faithful to the original Japanese; Tyler’s even manages to capture the roundabout sentence structures that characterize the Japanese language (at least to us English speakers).

And it’s not just the small details that matter in translation, either—one scene that Waley interprets as a jovial lovers’ meeting, Tyler interprets as a rape: it just goes to show you how much power the translator has in their interpretation of a book.

Harry Potter

With over 450 million copies sold, Harry Potter is one of the most widely-read children’s books of our generation—and it’s translated into an astounding 67 languages. Heck, there were even translations between the British and American editions—I still remember getting into a heated argument with my friend over whether the first book was subtitled: “The Philosopher’s Stone” or “The Sorcerer’s Stone.”

As the books grew in popularity, the publishers made more of an effort to preserve the original dialect. No more was “Mum” changed to “Mom” (I have an early edition of The Sorcerer’s Stone, where Ginny calls Mrs. Weasley “mom,” and it never fails to jar me). Though I’m glad that the subsequent editions kept their Britishisms, I would have appreciated a glossary every once and a while: it took me years to realize that “bogey” was British for “booger.”

As the books grew in popularity, the publishers made more of an effort to preserve the original dialect. No more was “Mum” changed to “Mom” (I have an early edition of The Sorcerer’s Stone, where Ginny calls Mrs. Weasley “mom,” and it never fails to jar me). Though I’m glad that the subsequent editions kept their Britishisms, I would have appreciated a glossary every once and a while: it took me years to realize that “bogey” was British for “booger.”

Luckily, being bilingual myself I have a cornucopia of books available to me in both English and Spanish, and more than once I’ve come across a word or phrase that didn’t translate quite right, whereas some spoke to me even more than they did in the original language. The job of a translator isn’t an easy one, and certainly not one I envy, but it’s a wonderful thing that helps open up entire new worlds of literature, across borders, cultures, and languages.

Written by Marcel De Vivo

1 comment on “Marcela De Vivo”